Editorials and Articles Archive

Allen's Wrench (Part II)

Kris Allen's win presents AI with a golden opportunity. Will the producers take it?

30 May 2009

When last we left our heroes, Final 9 Week had just concluded. Meghan (Joy) Corkrey was on her way home to Utah with a respectable ninth-place finish, a stage pass to the summer tour, and about 15 different name tags. Adam Lambert and Danny Gokey, along with perhaps a fading Lil Rounds, were presumed by almost every American Idol pundit to be far ahead in the race for the Season Eight crown. And the rest of the field? Well, they were doing what most of the midcard does every year: desperately trying to figure out some way, any way, to get the voters' attention before they too found themselves leaving on a Midnight Plane To Georgia (from which, with any luck, they could catch a connection out of Hartsfield to wherever it was they were actually from.)

Except this year, something strange was happening behind the scenes. At least one of the understudies, unbeknownst to anyone including himself, might have been playing a leading role all along. In fact, if our numbers are correct, quiet Arkansas blues-folkie Kris Allen, starting from absolute scratch, had already built the broadest fanbase of any contestant by this point in the season. If he could continue winning over viewers, and if he could devise a means for converting his newfound popularity into honest-to-goodness votes, he might even pull off the impossible and become the most unlikely, unhyped, unexpected Idol champion ever. Which he did. Which, uh, kind of ruins the suspense for the rest of our story. So just forget we mentioned that, okay?

Anyway, if you haven't already done so, now would be a really good time to read Part One of this saga. These past two weeks at WhatNotToSing.com, we're trying something a little bit different, falling somewhere between a scientific experiment and a simulation. ("Sims IV: The American Idol Edition! Vapid Judges Included!") Using the web approval ratings and standard deviations we compiled for every performance, we're attempting to model how the Final Three's fanbases evolved over the course of the season. We began with the reasonable premise that a contestant's popularity after any given show, ignoring any offstage factors, is some function of (a) his popularity coming into the week and (b) how well his performance(s) were received that night. We guessed at a few basic parameters, cranked up the engine, and we're seeing where it takes us. We sure hope it's not Hartsfield.

Allow us to point out yet again that this entire exercise, to borrow a phrase from Philadelphia sportswriting legend Bill Conlin, comes with more warning labels than a carton of Olestra cigarettes. We don't really know what parameters to use. We do realize that offstage factors can't be ignored, though we tried to account for some of them at the outset. Most importantly, we don't claim for one moment that the inclination bars we're generating bear any resemblance whatsoever to the actual weekly vote totals. Perversely, a contestant's popularity is only one of many factors that goes into a voter's decision-making process (which we'll discuss in due time.) So the specific percentage values you see are to be taken with a grain of salt. Focus instead on the relative movements of the bars from one episode to the next, which we believe are both realistic and enlightening.

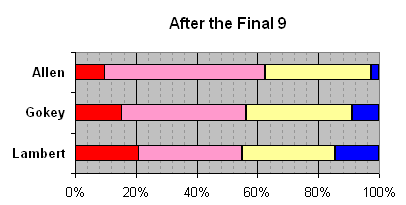

We'll pick up the story with the Final Eight. While the stagehands are busy setting up blue lighting and a chair for the last performance of the night, take a moment to remind yourself where our three guys stood coming in. Don't worry, your Tivo won't cut out too early again. Unlike the directors of American Idol, our staff knows how to tell time.

The Mid-Finals

Gokey and Allen were the first two singers out of the chute on Year You Were Born Night. Neither had dropped below 50 all season, but that was about to change: Stand By Me (44/19) and All She Wants To Do Is Dance (49/16) broke up their respective perfect games. Even so, a combined seven points off par wasn't the end of the world, particularly since Scott Macintyre picked that night to dig up a song that most listeners wish he'd have let rest in peace. Lambert, however, closed the evening with a rhapsody in blue: Mad World (92/19), one of the highest-rated performances in the history of Idol. Almost as significant as the showstopping approval rating was the fact that he'd gotten his standard deviation down to something resembling normalcy. Not only did that help him take the overall lead in our model, but for the very first time he no longer had the largest Cold segment. More voters wanted to put the fabled Go in Gokey.

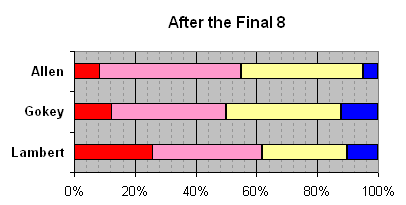

With roughly one-quarter of the electorate going loco for Lambert, Allen needed a major stroke of luck just to stay in the race. He got it in about the weirdest way imaginable. With overtime shows now a weekly occurrence, roughly 24,999,900 American Idol viewers felt the only sensible solution would be to have the four windbag judges SHUT THE HELL UP ALREADY! The other 100, alas, all worked for 19E and Fremantle. They hit upon the delightfully dumb idea of having only two judges critique each performance on Songs From The Cinema night. Gokey and Lambert drew Paula and Simon, for better or for worse. Like many of his performances, Lambert's Born To Be Wild started out well and ended as (choose whichever you wish) another virtuoso display of Lambert's breathtaking range / a screechfest. His 68 rating was perfectly decent and the highest of the night, but his s.d. nudged back up to 23. Gokey, meanwhile, dragged a harp onstage for Endless Love (35/18) and departed with his first 2-star rating of the season.

Allen, who drew Randy and Kara as his arbiters, chose the only contemporary song of the night: Once's Oscar-winning dreamlike ballad Falling Slowly (64/25). In what EW's Michael Slezak later termed, "...possibly the worst critique in the history of Idol", Randy dismissed Allen's effort as "pitchy" and said it "never quite caught on." Kara disagreed. Simon pointedly disagreed the next night, calling it "brilliant". And, the Idolsphere disagreed too...with Randy and each other. At 64/25, it marked Allen's highest lifetime s.d....and, we'd venture to say, it was the performance that saved his season. Fact is, Oscar or not, most viewers weren't familiar with the unusual song and had no clue whether he'd sung it properly or not. Talk of "Falling Slowly" dominated the Idolsphere, with many people not normally in Allen's camp rushing to his defense. Several music journalists later chimed in with glowing reviews of the performance, and bloggers took note of the news that Glen Hansard And Marketa Iglova's original version charted highly on iTunes the next day. For an unhyped contestant who needed a shot of buzz in the worst way, it was just what the doctor ordered, and it set the stage for what was to come the following week.

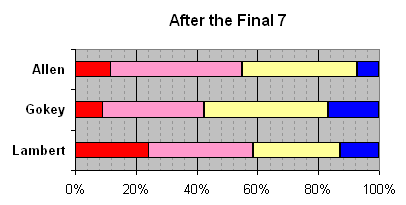

Because the judges had used their Save the week before, Disco Night would be another Final Seven affair. Lambert put his theatre background to good use, turning If I Can't Have You (78/18) into an old-fashioned torch number that just missed 5-stars. Gokey bounced back a bit after a couple rocky weeks with September (52/19), his first significant jump in approval rating all year. And Allen, in his pre-performance chair chat with Ryan Seacrest, casually mentioned that he'd chosen Donna Summer's She Works Hard For The Money. Excuse us? But Ryan (whom we're pretty sure was a secret Allen fan) calmed everyone by telling viewers, "I think you're going to like this." And, he was right: Allen had rearranged the disco anthem into a Tom Waits/acoustic Bruce Springsteen-style blues piece that resounded with recessionary America. At 85/15, it was the highest-rated performance of the night. Allen had pulled far ahead of Gokey by this point and was finally starting to gain back some ground on Lambert.

As we've been incessantly reminding you, the popularity bars we're publishing are not voting predictors. They're more like potential energy: they very roughly approximate the share of voters who can be persuaded to dial your number if the mood so struck them. What motivates a voter? Love, satisfaction, sympathy, anger, inertia, fear, you name it. In the case of Gokey, we believe that his heart-wrenching backstory and earnest personality brought him a large and motivated fanbase early, and that those people stayed on his bandwagon throughout most of the season. He may not have picked up many new fans along the way, but with the possible exception of "Endless Love" – and really, a 35 is hardly train wreck territory – he'd done little to shed any of the ones he'd started with.

On the other hand, Allison Iraheta (you mean you thought we'd forgotten about her? For shame!) had completely different dynamics to deal with. Like Allen, she started with virtually no fanbase. Unlike the rest of the Final Five, she was female and Hispanic, two traits which previous Idolmetrics studies have shown, sad to say, to be mild drags on a contestant. Being only 17, she came off to many viewers as being the least loquacious and least eloquent of the bunch. (Yes, we've seen her Idolatry interview; yes, those perceptions were obviously crazy wrong; but yes, that's what a great many people believed at the time.) And, sporting the most unusual appearance and fashion sense of the group, Lambert included, she was somewhat polarizing in her own way. Still, her string of consistently solid performances had earned her a worthwhile fanbase. So why did she keep ending up in the Bottom Three? Because for some reason, probably a combination of the ones we just mentioned, her admirers were not as inspired to vote for her as they were the Three Amigos.

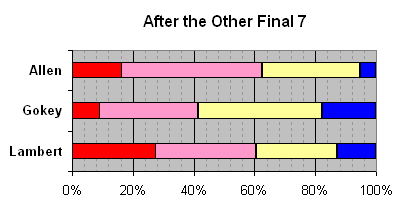

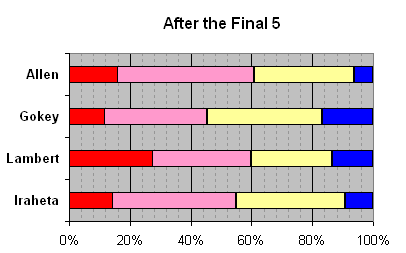

Nothing of simulation interest happened on the excellent Rat Pack Standards episode (the gap between first and fourth place was all of 17 ratings points), so let's show you where the four front-runners stood at this point:

Even after we tried taking into account all those negative factors, Iraheta would appear to be ahead of Gokey and not terribly far behind Lambert and Allen. Clearly, she was popular enough that people would vote for her if they had a good reason to do so: a great performance, a Bottom Three Bounce, etc. Final Five week gave people an additional reason: the Sesame Street Effect. With Lambert and Gokey presumed safe, most viewers saw the balloting that week as a referendum between Iraheta, Giraud, and perhaps Allen. Iraheta was considered most in jeopardy, and that proved enough of a motivation that she finished in the Top Two. (In fact, we wouldn't be surprised if she was in the Top One.) Gokey was safe, while Allen and Lambert, shockingly enough, made their first and last trips to the Bottom Three.

If you believe our popularity bars are even close to accurate, then there's really only one conclusion that can be drawn from the Final Five results: Lambert, Allen, and Iraheta were largely sharing a fanbase. Gokey, in contrast, appears to have had his voters mostly to himself. The nutty American Idol voting system strongly favors a contestant with few natural competitors. The producers and judges may have been misinterpreting this for months as a belief that Gokey's plurality meant America's majority, which was certainly not the case. (And if you say that a first-year Statistics major could've performed some elementary data analysis on the individual phone numbers to spot the reality, we retort that we are talking about American Idol, an outfit that still hasn't figured out how to count to 60 minutes in an hour. Please.)

A Brief Interlude

Before we get to the last three episodes of the season, here's something to consider. Cannon fodder contestants begin in anonymity and usually depart long before America remembers they were even there. (Quick: in what season was Nicole Tranquillo a semifinalist?) Nothing is more valuable to them than time. Heavily-promoted contestants can set the cruise control for a week or two if they choose, but fodderites have to outsing the competition each and every week in the early going, when one misstep might get them sent home. The weaker the competition, then, the better.

Which brings us to another stroke of extraordinarily good fortune enjoyed by Allen (and Iraheta.) Nobody knows how Ricky Braddy, Felicia Barton, Ju'Not Joyner, Jesse Langseth or any other semifinalist would have fared if they'd made it through to the finals. However, we do know how 19E's actual 11 pre-chosen finalists did in those first few critical weeks. Below is a table showing the approval ratings of all 23 performances by the first seven eliminated contestants during the AI8 Finals, with the 50+ performances conveniently marked in green. We present it without comment, save to quip that with enemies like the producers, Iraheta and Allen really didn't need many friends.

| Contestant | F13 | F11 | F10 | F9 | F8 | F7(i) | F7(2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lil Rounds | 74 | 37 | 42 | 36 | 26 | 17 | 28 |

| Scott Macintyre | 39 | 34 | 23 | 43 | 16 | ||

| Megan Joy | 28 | 43 | 15 | 11 | |||

| Michael Sarver | 45 | 26 | 21 | ||||

| Alexis Grace | 77 | 44 | |||||

| Jasmine Murray | 38 | ||||||

| Jorge Nunez | 24 |

(By the way, our Philly homegirl Tranquillo was a contestant in Season Six.)

The Sprint To The Flag

If our numbers are right, then despite starting from the last row of cars, Allen had stormed through the pack and was now on the lead lap, running bumper-to-bumper with Lambert. Clearly his deficit among Hot voters was too much to make up in three weeks, so to win, he'd need to pull well ahead on Warm ones. We were also reaching the point of the season where Cold voters might play a spoiler role. You have been watching those blue bars, haven't you?

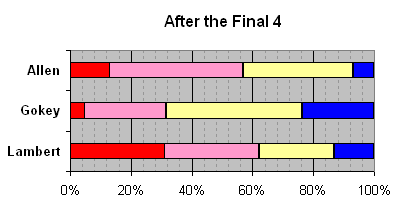

Rock 'N' Roll Night will forever be remembered for The Scream. Whatever the ultra-consistent Gokey was thinking when he chose Dream On (9/13), we really don't want to know. It turned into one of the most memorable train wrecks in Idol history, and in a weird way, it upstaged a rare and spectacular feat by Lambert. He became just the sixth contestant to post two five-star ratings in the same episode, opening the show with Led Zep's Whole Lotta Love (82/23) and closing it with a memorable duet with Iraheta on Slow Ride (86/15). (Clay Aiken, LaToya London, Fantasia Barrino, and Bo Bice twice, if you're wondering.) Allen turned in a so-so Come Together (46/20) and a sloppy duet with Gokey on Renegade (33/19). For multiple song weeks, we choose the performance by each contestant that we think had the most impact on the electorate; if the two performances seem about equal, we take the average. Here, we used the three guys' solo numbers, so:

It would seem at this point that Lambert had the competition in the bag...but hold on. Gokey's meltdown overshadowed all else this week, to the point where we're not entirely sure anything Lambert or Allen did made much of a difference. Furthermore, Gokey had received unusually kid-glove treatment from the judges after "Dream On" ("...an A++ for effort..."??!), which triggered a monstrous backlash across the Idolsphere. He was being vilified as a teachers' pet in many circles, and some of that outrage appears to have spilled over to Lambert's desk as well. We think a great many casual voters were now highly motivated to vote for Allen, if only to deny Simon & Co. the Finale pairing they seemed to be directing America to give them.

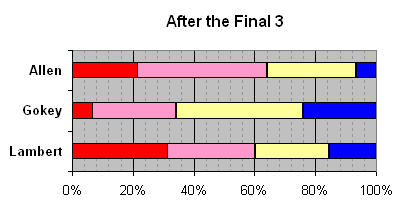

Fans who purchased Lambert's MP3 of One after the Final Three show reported that it built smoothly from a soft beginning to a full-rock ending. Perhaps so, but when compressed to 90 seconds, the abrupt volume change that Lambert employed was jarring to many listeners. At 47/27, it was the last combination the San Diegoan needed as he tried to run out the clock: his first sub-50 approval rating of the season, coupled with another massive standard deviation that would polarize the electorate even further. His second performance that night, Cryin' (65/23) was marred by a bizarre sound mix that left him and a backup singer brawling over the melody. None of this would have mattered had Allen gone quietly into the night. Instead, knowing he needed a game-changer, pronto, he pushed all-in with as bold of a song choice as Idol has ever seen: Kanye West's rap hit Heartless (85/15), blown up and pieced back together as an angry acoustic R&B number featuring just Allen and his guitar. And over the next 90 seconds, America slowly came to realize that whenever they exclaimed, "Kris Allen's singing WHAT??!" to their TV screens, it meant something very special was about to happen.

In wrestling terms, what America witnessed was a "reversal": Allen, nearly pinned, had flipped his opponent. And, because his cumulative standard deviation was far lower than Lambert's at this juncture (meaning that many fewer voters had firmly made up their minds about him), his tour de force had more of an impact on his popularity meter. Still, it was close. As we wrote a week ago, Allen seemed to have the broader fanbase but Lambert had the deeper one. The two guys' Cold bars were now firmly in play as well, and Lambert had an unwanted lead there. Nonetheless, we don't think Allen had quite sealed the deal yet. He still needed to give million of casual voters, particularly Gokey's rooters, a reason to believe he deserved the title of AI Champion.

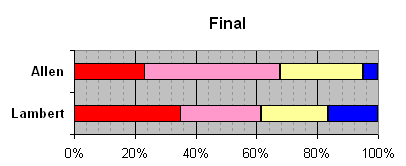

He did. His reprise of Ain't No Sunshine (88/13) in the Finale – this time with a full grand piano on a big stage, and with 7,000 people in the Nokia Theater audience hanging silently on the dramatic last few notes – no doubt convinced a lot of people that he was the Real Deal. In contrast, Lambert, who'd added some nice dramatic touches to Mad World (79/19), was in some ways handcuffed fatally by his gargantuan "sigma". It really made no difference whether he sang well or sang poorly; base opinions of him had long been set in stone. If he went with a safe performance, he might dissuade a few of his Cold group from voting for Allen, but then some of his Hot ones might not be as inspired to vote for him for four hours straight. If he unleashed the raw power vocals one last time, as he did on A Change Is Gonna Come (63/26), he'd extend his red bar but also his blue one as well. It was a quintessential Hobson's Choice situation set to music: damned if he wailed, damned if he didn't.

Yet for all of that, we still think Lambert had one last hope. He and Allen would close the show by singing the traditional Original Winner's Song™, providing the one and only chance all year for viewers to make an apples-to-apples comparision of the two men. Lambert was by far the more vocally gifted, and he had to remind America of that fact quickly. "Listen, Kris is a great guy and he's a brilliant musician and arranger and all. But this is a singing competition first and foremost. Let's see him do this." Unfortunately for him, Lambert's rescue chopper never got off the ground. No Boundaries turned out to be an appalling song, even by OWS standards. America watched in horror as first Lambert struggled with it theatrically ("What a terrible melody this song has, Gladys!") followed by Allen succumbing to it soulfully ("Good heavens, Harry, the lyrics are even worse than the tune!") It's impossible to mount a comeback by being left as the lesser of two roadkills. One night later, Allen became the eighth American Idol. Just don't call it an upset.

Post-Mortem

What we found most interesting about this little math experiment was how dramatically it illustrated the consequences of all those ultra-high standard deviations Lambert had been churning out. Note carefully how his pink-to-beige dividing line barely budged over the last six weeks of the competition, no matter what he sang or how well he sang it. Either you already liked him or you didn't, and all he could really do was change the depth of those feelings as reflected by his Hot and Cold segments.

Ironically, Allen's early anonymity wound up working strongly in his favor by the end. Unlike Lambert, he could and did sway people's opinions of him even in the middle of May. That not only allowed him time to become comfortable on a big stage, but also to listen and adapt to what analysts were saying about him. "Heartless" may have come off as a thunderbolt from the blue, but in hindsight it was merely the last, logical phase in Allen's evolution as a performer. The eye-opening thing about it wasn't that it showed he had a gift for rearranging songs cleverly. Honestly, most viewers had figured that out weeks ago. Rather, it was the revelation that the diminutive college student who'd been preciously dubbed "Pocket Idol" by his fans had, in fact, two of the biggest brass ones that the AI stage had ever seen.

Regardless of whom you were rooting for, you have to marvel at the astounding Series of Fortunate Events that allowed the unhyped Allen just to get into a position to win. Note particularly how many of them involved gadgetry from the producers that blew up in their faces, as if they'd spent the entire winter shopping from an Acme Products catalog they'd borrowed from Wile E. Coyote. But do not mistake his run of good luck to mean that Allen's triumph was in any way a fluke. Left for dead by the producers coming out of Hollywood, he patiently built the widest fanbase of any contestant, then figured out a way at the last moment to get them to rush to their telephones. Yes, some percentage of his votes in the Finale were undoubtedly due to homophobia, ignorance, and misguided religious zealotry, and that's disturbing. But then, probably quite a lot more were due to a backlash against the overbearing judges, and honestly now, whose fault is that? We can only guess at this, but based on our data, all of these non-singing factors probably meant that what would normally have been a very close win for Allen was in fact a blowout.

That's why we believe firmly that Kris Allen broke American Idol. On a show that works tirelessly to scrub the "reality" out of Reality TV, this outcome clearly wasn't supposed to happen. Coupled with some of the results from Season Seven, it demonstrates that many viewers of Idol are now in open rebellion against the producers. (Our friend The Idol Guy pointed that out to us, and we don't want to run with it too much further because it'll be a subject of his own editorial shortly.)

For now, we'll just add this: "Heartless", and particularly the forget-the-band / forget-the-fancy-lighting / forget-the-special-effects way Allen staged it, might someday be remembered as the seminal performance of the Third Idol Epoch. In it, successful contestants not only have to be great singers and musicians, but also savvy enough to figure out ways to do an end run around the producers' scripts and focus groups. Perhaps Ricky Braddy and his now-famous The Braddy Bunch website will be considered the earliest pioneer of the Third Frontier: "If 19E refuses to promote me, then dammit, I'll do it myself." Many AI8 semifinalists aggressively used YouTube, along with Facebook and other social networking sites, as a marketing tool this winter to attract fans. How sad is it that American Idol, a show that purports to be a grass-roots competition for young American singers, has gotten so far off course from its mission? Marginal contestants with compelling backstories or hot personalities get the lion's share of the promotion, while others with recording-quality voices are essentially relegated to begging for votes on the Internet.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Allen's win leaves the producers at a major crossroads. For the past couple of seasons, and in particular this one, 19E has treated the show as less of a singing competition and more of an extended infomercial for their newest prospective clients. The blatant manipulation, the pimp pieces, the Wild Card "casting" process, the reality-challenged judging, the odious Judges' Save rule: they're all merely tools for Idol Headquarters to keep those fickle voters from getting in the way of their expensive marketing campaigns.

Where do they go from here? Ramping up the manipulation levels is not a option. For one reason, we're not sure it's even possible. For another, the last two winners came out of nowhere despite all the backstage puppeteering. For a third, and probably the most important, fed-up viewers are already tuning out at a worrisome clip.

One possibility is for Simon Fuller to call his staff into the office and shout, "Underdogs! David Cook! Kris Allen! That's what America wants, and by golly, that's just what we'll give 'em! Ken, you go out this summer and find me a bunch of telegenic dark horses with no interesting backstories! Ceci, you have your writers come up with promo clips that spotlight how forgettable they are! My God, it's worth billions - why didn't we think of it before!"

We hope they go a different route. We say it's time for American Idol to go back to its roots. The most important lesson to come out of Season Eight is that the show's fans are tired of being led by the nose. People tune into Idol to hear great singers sing great songs in interesting ways, and to be critiqued by fair and competent judges. Musical variety, demographic diversity, and attractive personalities are all important; we wouldn't dream of claiming otherwise. But they're the seasoning, not the main course. Pre-scripting the outcome is anathema to everything Idol is and ought to be about. That's the most important implication of Allen's victory, and if the producers comprehend it, they'll also realize that the bizarre war they're actively waging with their viewership is one they cannot win and which they have no business fighting in the first place. Nothing at the moment is more important to the future of the franchise.

Kris Allen may have broken American Idol, but he, along with Adam Lambert and Allison Iraheta and in an odd way even Danny Gokey, also showed us the path to saving it. Next weekend, we'll take a closer look at where that road ought to lead.

- The WNTS.com Team