Editorials and Articles Archive

gleeful

Why has Season Eleven thoroughly reversed a longstanding Idol trend?

29 April 2012

Once is happenstance. Twice is a coincidence. Three times is enemy action. So went the mantra of James Bond's notorious nemesis, Goldfinger, in the eponymous 1959 novel by Ian Fleming. A decade later, Arlo Guthrie featured a variation of Goldfinger's quip in his 18-minute musical romp, "Alice's Restaurant", and it's been recycled in popular culture countless ways ever since. (Incidentally, one might safely presume we'll never have to endure Guthrie's masterpiece compressed to a minute-forty on American Idol...but then again, we've now heard Bohemian Rhapsody done so three times. No song is safe where AI is concerned.)

Neither Fleming nor Guthrie bothered to extrapolate Goldfinger's Law beyond three, but we imagine they'd agree that ten times is a hard-core, dyed-in-the-wool, no-doubt-about-it Trend. Such is the case when it comes to song age on Idol.

Ten seasons.

Ten thoroughly different casts of contestants.

Ten songs in total that have been performed on the show. (OK, we kid here. A little.)

Ten times the same correlation holds true: the older the song, the higher the average approval rating. Each season. Every season. No exceptions, Mr. Bond. No exceptions.

Regular readers know how much this little fact drives the staff of WhatNotToSing.com insane. Despite your senior editors' depressing, AARP-ready ages, we want to hear modern-day music on AI, even if we can't stand much of it. (If any contestant ever does a Ke$ha or Nicki Minaj song, we might cheer and vomit at the same time. No, really.) We even wish the producers would drop their outdated ban against rap and hip-hop. Call us crazy, but we suspect that when most urban kids visit iTunes today, they're looking for the next Kanye West, not the next Luther Vandross.

Yet for all of our teeth-gnashing, we couldn't deny the Ten-for-Ten Trend. American Idol viewers have always preferred performances of older songs to newer ones. To quantify this via a linear regression: for every 10 years of song vintage, the average contestant could expect an additional 1.8 points on his or her approval rating. Sing something from the early 1970s and you essentially enjoyed a 7-point head start on your contemporary-singing competitor.

We'd discussed this in several previous editorials, in particular Morton's (Tuning) Fork, and we ruefully concluded that there was little to be done about it. Indeed, that's why lately we've been harping on song freshness rather than calendar age: if we had to hear young-'uns sing golden oldies to us every Wednesday night, then for the love of mercy, at least let them be ones we haven't heard on AI six times before. Death by skin gilding is way preferable than having to sit through I Have Nothing again. No, really.

![]()

![]()

![]()

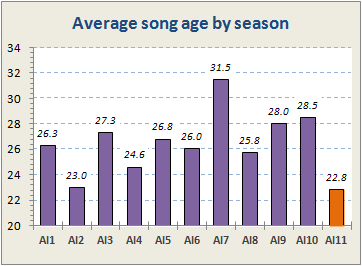

With this in mind, you can imagine the joy in our hearts over what's transpired in 2012. Faced with stiff competition from The Voice and its ilk, all of which seem to have far less difficulty getting modern songs cleared for the airwaves, and facing an even stiffer backlash from their chronologically fed-up fans and bloggers, the Idol producers bit the golden bullet, as it were. They've dared to go low. In fact, as this updated chart from Morton's (Tuning) Fork shows, Season Eleven has actually taken over the lead for the youngest catalog of songs featured in any season thus far.

(Incidentally, the usual disclaimers apply here: these numbers include no reprises, no anythings from a Finale episode, and we're even accurately counting duets as one performance rather than two, finally.)

Risky? Maybe. But, lo and behold...it's working. At least for now, and at least a little.

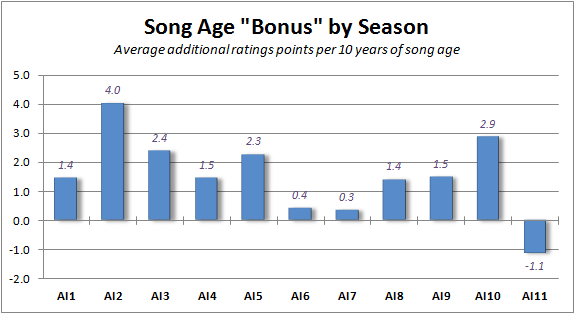

The chart below shows the correlation between song age and approval ratings through the first eleven seasons of American Idol. Every horizontal line represents one ratings point per ten years of song age. The upward bars signify that older songs rated out higher that season than newer ones, and the downward bar...ahem, singular...indicates that younger songs scored better. AI11 is the first season to bend the age curve, as it were, and its sustained success with 21st Century material has dropped the historical advantage for old songs from 1.8 points/decade to 1.5. Pretty heady stuff.

Had we any common sense whatsoever, we'd end the editorial right here and count our blessings. But, alas, we can't leave well enough alone. Why has Season Eleven broken an "enemy action" that even through last season showed no signs of ending any time soon? Obviously, we have nowhere near enough data to prove or disprove anything, so allow us simply to throw out three conjectures.

- It's just happenstance. Call this one Goldfinger's Hypothesis. Season Twelve might revert to form and post another huge upward bar in that chart, and someday we'll look back at AI11 as nothing more than a welcome oasis in an otherwise endless desert of Old. This is perfectly plausible, of course, but our (perhaps wishful) gut feeling says no, something significant has truly changed in the Idol landscape.

- It's the contestants. Perhaps this year's crew is unusually myopic musically. They're less able to connect to songs from the previous century, but better able to pick out strong contemporary material. Considering that several of them were unfamiliar with virtually anything from Billy Joel's songbook, this too is quite plausible. Still, our money is on:

- It's us, the fans. Our attitudes have changed, particularly among older viewers. All of us have heard classic songs covered frequently and in many different styles, and we've learned to enjoy the variety. But until recently, that was untrue of modern music. With limited musical outlets beyond commercial radio available to most of us, we were used to hearing newer stuff performed one way and one way only. But then came Pandora and Last.fm and iTunes and YouTube and karaoke bars and the indie music revolution. Like everything else in our Internet-powered world, the elevation of a song into Great American Songbook status has accelerated dramatically.

If the third hypothesis is true, then perhaps Fox themselves can lay claim to some of the credit. Besides American Idol, it's biggest contribution to North American pop culture circa 2012, for better and for worse, is its other mega-hit series, Glee. Glee is essentially an old-fashioned stage musical, serialized, with modern songs and a few PG-rated story arcs. Every performance is a cover, usually compressed and frequently stripped down or heavily rearranged.

Once upon a time, the musical was the dominant form of stage and film entertainment, and most of them were constructed out of recycled material. (Don't believe us? The consensus greatest movie musical ever, Singin' In The Rain, featured exactly two new songs. Everything else in that sublime film was a cover.) Glee isn't going to bring back those glory days, but it has introduced the notion that unusual covers, even of newer songs, can be enjoyable. Note too that the only previous significant dip in the Blue Bar Chart came in Seasons Six and Seven. What was the big pop culture phenomenon among younger Americans in 2007 and 2008? The High School Musical movie series. Correlation doesn't prove causation, we know, but it still makes us wonder.

![]()

![]()

![]()

At any rate, and whatever the reason, we're cautiously content. We hope, however, that the five remaining finalists keep in mind that the producers are watching them closely. The AI11 contestants are enjoying the most wide-open themes in franchise history, and the change came on so abruptly that Nigel Lythgoe and Ken Warwick are almost surely (and perfectly understandably) nervous about how it will all play out. The Idols are doing nobody – not the viewers, future contestants or themselves – any favors by choosing songs that middle America finds too inaccessible or, as Simon Cowell would bluntly put it, too indulgent. With great power comes great responsibility, and all that.

Still, one way or another, here's hoping that Modern Music Idol is here to stay. Even if it someday includes #$%^&* Ke$ha. Yes, really.

Addendum

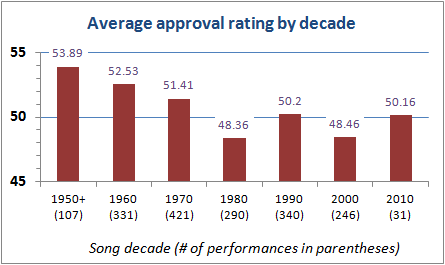

Before we conclude this week's editorial, we feel we ought to update another chart from Morton's (Tuning) Fork, both to align with our improved Idolmetrics criteria (no reprises, no Finales, duets counted as one performance) and to underscore just how adept the AI11 crew have been with modern material.

Here's the newly calculated Average Approval Rating by Song Decade analysis, with everything from 1959 on back counted as the 1950's. Note that the Eleveners have brought the 2010's back among the living, leaving only the 1980's (where godawful song choices have been the depressing norm) and 2000's underwater.

- The WNTS.com Team