Editorials and Articles Archive

Highway 4.2 Revisited

Has the "Guy Bonus" increased since our original Idolmetrics study?

1 April 2012

The trend can't be ignored. Season Eight: seven guys to three girls in the 2009 Final 10, leading to four of the Final 5, and all of the Final 3. Season Nine: six-on-six at the outset of the finals, six-on-two within a month, and the Final Five once again comprised four guys and one lonely girl. Season Ten: the first five finalists out were all female, and though the two surviving ladies hung on all the way to the Final Three, they couldn't prevent a fourth straight male champion. Season Eleven: American Idol unearths the strongest collection of female singers since the Andrews Sisters; a sextet so good that the tenth-place finisher pitched a perfect game and the Idolsphere's response was to collectively shrug and mumble, "Too bad, but it was her time to go." And the Final Nine still had more guys than girls!

In January of 2009, WhatNotToSing.com published "It's A Man's Man's Man's World", our original study on gender bias, concluding that the average male has a 4.2% greater chance of advancing each round than a female with an identical approval rating. And, ever since, it seems that American Idol has been hell-bent on proving that we underestimated.

About this time last year we re-ran the experiment, and we discovered that the Guy Bonus had indeed risen...but only fractionally. Depending upon what assumptions we used, it was now right around 5%. That's not trivial, but its not insurmountable either.

We guessed that the reason AI men had suddenly seen their survival fortunes improve was because, as a whole, they'd sung a heck of a lot better than their counterparts from the first seven seasons. But, is that really the case? Let's revisit this topic, not only with updated numbers, but also with significant improvements in our methodology for isolating voter biases.

Men At Work

As you know, the last girl to get a confetti shower on American Idol was Jordin Sparks in 2007. Since then not only have four straight guys won, but the first three were cut from very similar cloth: alternative rockers in their mid-twenties with okay-to-good voices (by AI finalists' standards), strong pop sensibilities, and a gift for choosing strong material and then rearranging and presenting it superbly. Those three winners – David Cook, Kris Allen, and Lee DeWyze – form the holy triumvirate of the Third Epoch of American Idol.

Last season, teen country crooner Scotty McCreery rode a somewhat different horse to victory. While nowhere near as musically imaginative as his three predecessors, McCreery compensated by choosing a string of fresh-to-Idol songs that he knew his core base of C&W fans would appreciate, and then singing them well (if perhaps a bit too much the same) week after week.

Were Simon Cowell still at the judges' table, McCreery would likely have faced blistering criticism for his singlemindedness, not to mention his lack of vocal gymnastics and stage histrionics. But, this was now the Fourth Epoch; the Post-Simon Era; in which the judges have no desire to play kingmakers as long as a contestant was progressing in his or her own way with each performance. (Unfairly, because of McCreery's chromosome pattern and the fact that he played a little bit of acoustic six-string, some AI fans have lumped him with Cook, Allen and DeWyze in the category of WGWG: White Guy With Guitar.)

Considering that four of the first six champions were women, the past few years could be written off as a natural statistical correction. Except, as we noted in the first paragraph, the guys as a whole have done more than just win. They've been avoiding the voters' axe at a furious clip. Well, they've been singing better, no?

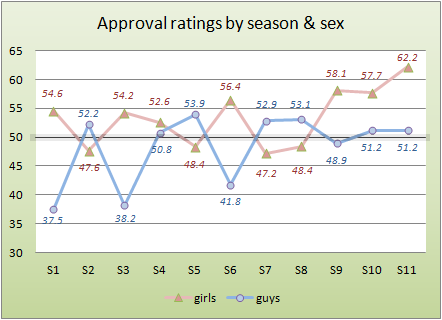

Uh...no. As the nearby chart shows, except for Season Eight, they really haven't. At all. In fact, it hasn't even been close. (Incidentally, we are only considering performances from "competitive" episodes consisting of at least one guy and one girl, and we're tossing out reprise and Finale performances; see the next section for a fuller explanation.)

Note that through the first eight seasons, there was a 100% correlation between which sex sang better and which one ultimately won. The guys came out ahead in AI2, AI5, AI7 and AI8. The girls walloped the guys in Seasons One, Three and Six, and they narrowly squeaked out a win in Season Four despite Bo Bice's best efforts. All was more or less right with the AI world.

Since then, however, that correlation seems to have gone south for the winter. In AI9, the two-woman tag team of Crystal Bowersox and Siobhan Magnus pretty much throttled the guys all by themselves, yet DeWyze emerged as the victor. (Remember, the semifinals that year ran for three weeks and, because they were sex-segregated, they're not included in the averages. Plus, the first four finalists out were relatively weak women, leaving Bowersox & Magnus to go medieval on the guys' butts week after week until they were ultimately ousted.) In AI10, once again it was the lower-rated girls plus Pia Toscano getting shown the door early, leaving Lauren Alaina and Haley Reinhart to slap the boys around merrily for over a month...but again, it was a guy, McCreery, who came out on top.

As for AI11, the 11-point gap is because the girls have been nothing short of filthy so far. But you already knew that.

As our colleague The Idol Guy observed this week, the elimination patterns the past three-plus years have been nothing if not predictable: weak girls first, then weak guys, then things settle down to something resembling normalcy. For whatever reason, undercard and midcard females on American Idol have not been able to build an early fanbase that would allow them to compete with their male counterparts. This, we'd say, largely explains the huge gender gap in the ratings: weaker guys get to sing more often.

So if the guys haven't gotten better lately, then what about that 4.2% figure? Surely it's gone up, but by how much? Let's find out.

Hear Me Roar

(If you haven't read the Perpetual Disclaimer for our Idolmetric articles in a while, it might not be a bad idea to review it now.)

Since this is our second go-around of the Gender Bias study, we won't bombard you with a ton of data. We will, however, quickly run through the improvements we've made in our methodology since all of our original Idolmetrics studies (a joint effort between WNTS and TIG) were published in the weeks leading up to AI8. They are:

- First and foremost, we have over three years of additional data to work with. That's huge, to say the least.

- Second, about two years ago, the WNTS Actuarial Department had what Dilbert's creator Scott Adams once aptly termed, "a blinding flash of the obvious." We began ignoring reprise performances and Finale episodes in our data sets. Simply put, they're useless. The former, with precisely one (1) exception, always rate lower (usually a lot lower) than the original performance. The latter are more of an exhibition than a competition, featuring a heavy dose of reprises plus those universally-loathed Original Winner's Songs™ that nobody, including the contestants, wants anything to do with. Good riddance.

- Third, since we're studying voters' biases, we thought it would be a good idea to ignore those episodes in which the producers didn't let their viewers, uh, you know...vote. Similarly, we now treat judges' saves and wild-card callbacks as garden-variety eliminations. Bottom line: if the voters tried to kick you to the curb on Results Night, we're going to assume you made it there.

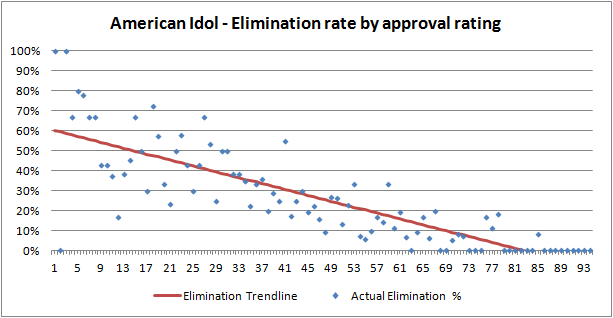

- Fourth, all of our calculations depend on the relationship between approval ratings and expected elimination rates. In the past, we'd used a very coarse formula to approximate this, which included some "holes" that we never adequately dealt with. For example, in a statistical quirk, no one has ever gone home on a night when their approval rating (or average rating, in a multi-performance week) was exactly 49. We're now using a continuous polynomial regression trendline, which is much more accurate (see the chart at the end of this section). If this paragraph came off as complete mumbo-jumbo to you, good news: it's over, and it wasn't that important anyway.

- Fifth, we now correct much more accurately for what we'll dub "uncompetitive episodes" – those in which all of the contestants are (say) male, or black, or Southerners,

or way out of tune, or otherwise offering no diversity in the variable we're trying to isolate. This was the biggest source of error in our original studies, as you'll soon see. - Sixth and finally (and perhaps most usefully to our readers)...well, we'll get to this is a moment.

So, let's proceed. First things first: we're going to re-run the 2009 study using our New-'n'-Improved methodology. That way, when we get around to the 2012 data, we can compare apples to apples.

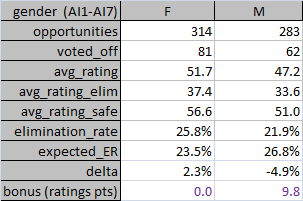

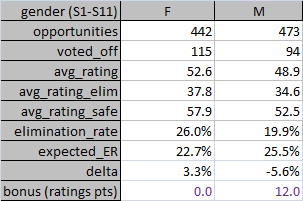

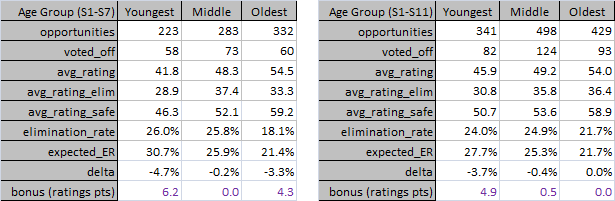

The chart at left sums up what we found. "Opportunities" represents the number of times a contestant of a particular sex was at risk of going home in a "competitive" episode (that is, one that had at least one member of the opposite sex.) "Avg. Rating Elim." and "Avg. Rating Safe" are the average approval ratings that each gender posted on performances in which they were voted off (including wild card callbacks & judges saves) and safe, respectively. "Elimination Rate" is simply vote-offs divided by opportunities, and "Expected Elimination Rate" is what our 11-season trend line suggests should be the bye-bye percentage for each gender's respective average approval rating. Lastly, "Delta" is the difference between the expected and actual elimination rates.

The bottom line is that we did underestimate the Gender Bias of the voters through the first seven seasons...and by quite a lot, too. The girls sang over four points better than the guys, yet they went home almost 4% more frequently when they competed head-to-head. When we properly isolated the Sex variable (eat your heart out, Alfred Kinsey), it turns out that the instead of a 4.2% advantage, it should have been 7.2% – the difference between the two delta values.

What does a 7.2% advantage in elimination rate mean? Given two contestants, a guy and a girl, who sing to an identical approval rating on a given episode, the girl is 7.2% more likely to be voted off the next night. Instead of 50/50, as one would expect if gender was completely irrelevant, it's actually closer to 54/46. And keep in mind: this advantage repeats each week, every week.

Still, even after all these years, expressing advantages in percentage terms seems a bit too...abstract. Why don't we express it in something more familiar to WNTS readers? Hence, we present that sixth and final improvement that we promised: we'll forevermore quantify the AI Gender Bias (and all other biases) in terms of approval rating.

The chart at section's end shows the scatterplot between one's weekly approval rating (the X-axis) and the corresponding chance of elimination. The slope of the red trendline is -0.007366, meaning that for every one additional point that America likes you, you are about 74/100ths of one percent less likely to go home the next night. Therefore...and we're going to warn you: this is really frightening...through the first seven seasons, the average woman needed to sing to an approval rating 9.8 points higher than the average man in order to have an equal chance of surviving the next night!

In a word: Yikes.

So what's happened in the three seasons since? Don't ask. The Gender Gap has only gotten wider. The table at right shows how we stand through all ten-plus seasons of AI. The guys' survival rate advantage (again, that's the difference between the two deltas) is up to 8.9%. And that means the Girls' Handicap is now 12.0 points. Remember that 11-point lead the ladies of Season Eleven currently enjoy? They're gonna need every bit of it and perhaps a wee bit more to have an even-money shot at winning.

Double yikes.

Ev'ryday People

Having redone this study for the Battle of the Sexes, we figured we had better re-run the numbers for our other demographic groups too. Our improved methodology was likely to produce different numbers, plus we wanted to see what happened in those other categories in the three years since. Here's what we learned.

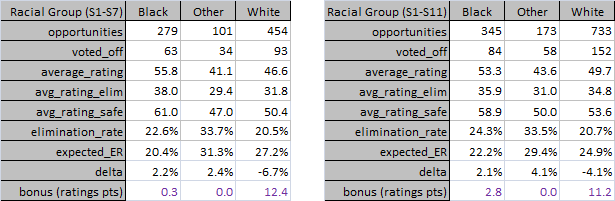

Age: In our original study, as now, we broke down contestants into three age groups: the youngest 1/3rd, the middle, and the oldest. The specific cutoffs for each group varied from season to season depending upon the audition ages. We found that the Youngest Third had an extremely slight advantage over the other two groups. We'd originally calculated it as 2.1%, or just inside our margin of error. But according to our New-'n'-Improved methodology, there was indeed a significant gap...it just wasn't where we thought it was. It turns out that the middle group, consisting of roughly 19 to 22 year olds, were at a 4 to 6 ratings point disadvantage over the other two strata.

Today? Thanks mainly to McCreery and Alaina, the kids have held on to their advantage, but it's narrowed all around. A teen Idol can sing about 4.9 points below their eldest rivals and still enjoy the same chance of survival. That's outside the margin of error (which we consider to be 3 ratings points) but we still wouldn't make very much of it.

Race: We consider an American Idol contestant to be one of White, Black, or Other. If you think the "Other" is ethnically insensitive, too bad – we simply have nowhere near enough data points for Asians, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders and contestants of mixed race to treat them separately. Three years ago, we calculated white contestants to have a 5.8% (8-point) advantage in survival rate over black contestants, and blacks to have a 3.4% (4.6-point) advantage over the Other group.

Well, we blew it. Our failure was that we didn't take into account the not-uncommon episodes, usually towards the end of a season, in which all the remaining contestants were white. One of them obviously had to leave, no matter how well or how poorly they all sang. Those non-competitive episodes inflated the white elmination rate artificially. (Side note: there has never been an American Idol episode in which every contestant was nonwhite.)

In our new methodology, the advantage of white contestants through the first seven seasons was about 9% over all others, regardless of race. That corresponds to a racial bonus of over 12 ratings points.

Things have thankfully gotten a little better since then, at least for African-American contestants. The gap between whites and blacks is down to 6.2%, or a "bonus" of 8.4 ratings points. Blacks have also opened up a 2% advantage (2.8 ratings points) over the Other group, but this is within the margin of error. And before you ask: yes, these numbers do include Heejun Han's longer-than-expected run in Season Eleven.

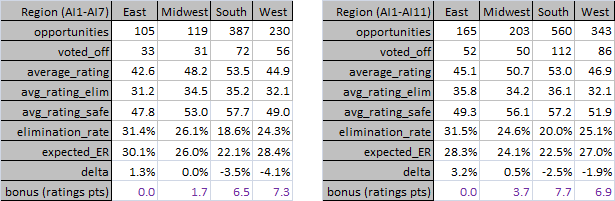

Geographical Region: This one seems trivial, but it's not. In our previous study we found that contestants from the Northeastern U.S. were at a pretty significant disadvantage (5.4% / 7.4 ratings points) to the rest of the nation, particularly the South. This time we'll be brief: even under our new methodology, the numbers through Season Seven changed only a little.

Nor have they changed much since. Southerners and Westerners are pretty much on even par with one another, but folks from Dixie have a 3% advantage (i.e., a 4-point bonus) over Midwesterners and a 5.7% advantage (7.7 points) over Easterners. To recycle a line from the previous article, your Philadelphia-based WNTS team responds: big deal. Our contestants can still beat up your contestants.

Pre-Finals Exposure: We saved this one for last because, we freely admit, this is still where we hope our readers will focus their outrage. Is America racist? Sexist? Ageist? Regionally parochial? Look, our guess is "yeah, probably a little of each, and maybe some more than others." But we're not entirely convinced that the voting patterns on a TV singing contest is the best vehicle for arguing for or against those points, anyway.

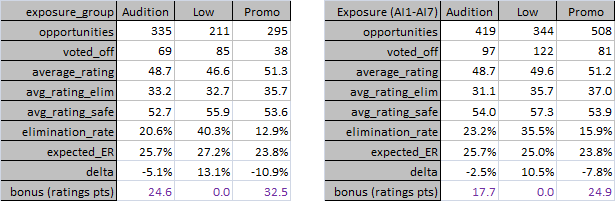

However, as we discovered way back in 2009, one factor trumped all others when it comes to long-term survival on American Idol, so much so that all of the demographic advantages and disadvantages were jokes by comparison. And that's the level of early exposure the producers gave each contestant in the weeks leading up to the semifinals. We divided the contestants into three groups: "Promo" (those who received an in-depth "pimp piece" during the audition shows), "Audition" (those whose auditions were aired more or less in full) and "Low" (those whose first significant face time to viewers came in Hollywood or later). We found that Pimpees had a small but significant advantage over Auditionees, and both cleaned the clocks of the Low group. Our new, more accurate methodology didn't result in any changes there.

Since then...well, by now you know how to read these tables so we'll just leave it to you. The best we can say is that things are getting better; the Low group has chopped about seven-and-a-half points off the Promo Bonus. But when a Promo segment effectively gives you a 25-freaking-point head start every week over the producers' cannon fodder, we can say with confidence that we'd rather be a little green hermaphrodite from Mars with a pimp piece than (almost) any other demographic combination you can dream up but with Low exposure.

The producers have the power to stop this nonsense. The fact that the gap is shrinking is a good sign. But, just from Season Eight on, the bonus for getting a pimp piece is still 11.7 ratings points over being kept under wraps until Hollywood. (The gap between Audition and Low has shrunk to within the margin of error.) And besides, the two biggest reasons for the improved state of affairs are named Kris Allen and Alison Iraheta. The two Little Cannon Fodders That Could from Season Eight are by themselves responsible for almost 3 points of the 7.6-point decline.

![]()

![]()

![]()

It's no secret that 19E would prefer a female winner this season. The commercial and critical success of the likes of Adele, Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Joss Stone, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, Florence + The Machine and many others have made the 2010's a better-than-usual time to be a talented woman in the music industry. The producers, however, are swimming against a riptide of unusually strong support for male contestants on AI. Even with a group of girls who are averaging – averaging! – four stars since the Finals began, we'd still say their chances are no better than 50/50.

How to correct for this? Other than continuing to stack the talent deck in favor of the fairer sex, perhaps the producers can't. One would hope that a singing competition shouldn't have to be divided into separate tracks for men and women, like the NCAA Basketball Tournament, but we're reaching a point in which all options have to be considered. After all, it's widely assumed that the Idol voting electorate is made up predominately of females of all ages. If they happen to prefer male singers to female ones, it's difficult to tell them to stop. Encouraging more male voters may or may not help the situation.

Countless women music artists through the years will tell you how much more difficult it was for them to make it in this business than for their male counterparts. No matter what the reasons for it, what we're seeing on American Idol might be nothing more than a vivid, painful, weekly reminder to the rest of us of what they've known all along.

- The WNTS.com Team